|

“There's

just no way to describe that. You just live from day to day or hour to hour.

You never know when your time's coming.”

|

|

|

|

|

Three

and a Half Years as a POW

|

|

|

-An

oral history of Arvil Steele

|

Home | Table of Contents | Previous Story | Next Story

Personal Profile | Video Interview

|

After

Arvil Steele completed the ninth grade, he quit school and joined the U.S.

Army. By Christmas 1940, he found himself stationed far from home in Iba,

Philippines. Mr. Steele’s first year in the South Pacific passed peacefully;

but, on December 7, 1941, the peace was shattered. On that fateful day, Arvil

was dining in the mess hall when, “Someone hollered, ‘The planes are coming!’”

He ran outside and looked up to see about a hundred planes. “They were silver

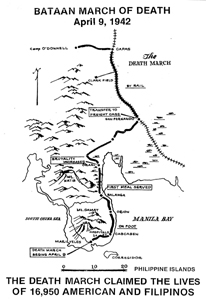

in this pretty blue Although Arvil was on a two-year tour, he soon realized that he would not be leaving on schedule. “I didn’t make two years. I got caught.” After the bombing of Iba, Mr. Steele’s unit moved to Manila where they were attacked again. This time, Arvil did not escape unharmed; a piece of shrapnel grazed his forehead. The American and Filipino forces soon found themselves outnumbered and outgunned. Mr. Steele estimates that around 25,000 Americans and 70,000 Filipinos equipped with World War I rifles had to face at least 100,000 Japanese soldiers with more modern weapons. As the fighting continued, food and supplies dwindled. “We were eating anything we could—snakes, monkeys, and just anything we could find,” he grimly recounts.

He remained at one camp for the duration of his bondage and won some favor with his captors. Arvil learned to speak Japanese rather well and was made a “Honcho,” the POW who instructed the new prisoners. At last, in 1945, Arvil Steele and his fellow POWs were liberated by American forces. Soon he was back on American soil and headed home to Texas. It took some time for Mr. Steele to adjust to life as usual. “My mother would tell people, ‘He’s just so quiet. . . .’ I just didn’t want to talk about it.” More than fifty years after his release, Mr. Steele is still haunted by the memories of his captivity. “I see things sometimes yet because I’ve seen some of the most horrible things.” Still, Mr. Steele is thankful for every day he is given to spread his story and ensure that this piece of history will never die. “I’m history,” he proudly declares. |

Home | Table of Contents | Previous Story | Next Story

sky,”

Arvil recalls. “That was the prettiest sight you’d ever seen . . .until you

saw those bomb bay doors open.” The Japanese attacked the Philippines just

hours after Pearl Harbor. “I knew—and they should have known—that war was

coming,” Mr. Steele reflects.

sky,”

Arvil recalls. “That was the prettiest sight you’d ever seen . . .until you

saw those bomb bay doors open.” The Japanese attacked the Philippines just

hours after Pearl Harbor. “I knew—and they should have known—that war was

coming,” Mr. Steele reflects.  The

situation continued to deteriorate and, finally, U.S. General Edward King

surrendered the American Forces on Bataan. In 1942, three and a half years

of captivity began for Mr. Steele. “[King] had to capitulate,” he says. “We

were just finished.” Mr. Steele goes on to describe the unfathomable living

conditions he endured. “You were never at ease. You never could sleep at night.”

Arvil and the other POWs were given pillows made of sawdust and straw mats

to sleep on. The men were forced to build a dam, working ten days straight

“from sunrise to sundown.” They would have the eleventh day off during which

they were permitted to bathe and were expected to clean the camp. “You had

no medicine whatsoever. If you got sick, and God wasn’t with you, you died,”

Mr. Steele says.

The

situation continued to deteriorate and, finally, U.S. General Edward King

surrendered the American Forces on Bataan. In 1942, three and a half years

of captivity began for Mr. Steele. “[King] had to capitulate,” he says. “We

were just finished.” Mr. Steele goes on to describe the unfathomable living

conditions he endured. “You were never at ease. You never could sleep at night.”

Arvil and the other POWs were given pillows made of sawdust and straw mats

to sleep on. The men were forced to build a dam, working ten days straight

“from sunrise to sundown.” They would have the eleventh day off during which

they were permitted to bathe and were expected to clean the camp. “You had

no medicine whatsoever. If you got sick, and God wasn’t with you, you died,”

Mr. Steele says.